Designing a Future That Works for All

March 7, 2023 - 9 min read

Biotech is not inherently neutral, but we can design it to be fair

With the coming of every technological revolution lies the promise of a better life for everyone. The Industrial Revolution led to lower prices, more goods, and higher wages. The Scientific Revolution of the 20th century dramatically improved the quality of life for countless people through the development of vaccines and cures for various diseases, the discovery of new forms of energy, and advances in industrial chemistry that provided new materials for manufacturing thousands of products. Most recently, the Digital Revolution enabled mass communication worldwide and provided democratized access to a previously unimaginable abundance of information, knowledge, and resources.

We are now at the dawn of an imminent Biological Revolution that promises to be the most important technological revolution to date, with the potential to impact all areas of our lives, from health to food, climate, manufacturing, and much more. But even with all of the hype coming from bioenthusiasts, the enormous amount of research being conducted every year, and the billions of dollars being poured into biotechnologies, there’s still another side of the coin we need to consider.

Yes, technological revolutions usually leave societies better off than they were before, but that’s never without some collateral damage. The Industrial Revolution, for instance, was the catalyst for massive population growth thanks to the overall improved quality of life that the new technologies brought, but at the same time, it involved child labor and inhumane working conditions and initiated a surge in global greenhouse gas emissions that continues to this day.

In the case of the Biological Revolution, the primary concerns are usually related to biosecurity and the misuse of biotechnologies to deliberately cause harm. There are also worries about the ethical considerations of using technologies like CRISPR for human genetic enhancement and the possible ecological consequences of the use of GMOs. But there’s something missing.

The general assumption is that technology is intrinsically neutral — it can be used for either good or bad and the outcome depends on the person or group who uses it. However, history has shown us time and time again that this is not entirely true.

Biased from the start

Everywhere we remain unfree and chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or deny it. But we are delivered over to it in the worst possible way when we regard it as something neutral; for this conception of it, to which today we particularly pay homage, makes us utterly blind to the essence of technology. ― Martin Heidegger

Biases are to humans what colors are to a rainbow. They are inherent to people and even though we can endeavor to become conscious of them, we can never totally get rid of them. Our biases shape the way that we think and ultimately the decisions that we make. Furthermore, biases are shaped by the context, culture, and values that surround us.

This means that when a technology is conceived or designed it will ultimately be a reflection of these biases. They may be unconscious or unintended by the people who created the technology, but in the end they are there.

Let’s take for example a seemingly harmless piece of technology: a bridge. During the early to mid-20th century, Robert Moses served as an urban planner for the New York metropolitan area. By overseeing the construction of parks, highways, tunnels, and much more, he was responsible for creating many of the city’s most iconic features. Yet the urban planning and infrastructure design were heavily influenced by Moses’ racist views. This can be seen in bridges that were purposefully designed to be so low that buses wouldn’t be able to pass under them, only cars. Because poor minorities were the ones that most commonly used public transportation, this prevented them from reaching Long Island’s beaches, allowing only those rich enough to afford a car to pass underneath.

Next, let’s take a look at what we could consider somewhat of a more unconscious bias: a “racist” soap dispenser that only works for white people. I seriously doubt that the designers of the automatic soap dispenser purposefully designed it to work this way. Instead, what most probably happened is that the dispenser was designed under the fair assumption that if you send a beam of infrared light from an LED, this will be reflected by the user’s hand and send a signal to the mechanism to dispense the soap. The thing is that the designers didn’t take into account the entire spectrum of people who would end up using the dispenser, including individuals with a darker skin color that absorbs the light instead of reflecting it.

The bottom line here is that technology is not neutral by default. It comes with biases and flaws that are a direct result of their creator’s context, values, and even the things they inadvertently omit. Ultimately, when considering the uses and applications of a technology, we should also take into account human biases and the responsibility and context of the designer because technology will always bring burdens along with the blessings whether we want it or not.

Also, the greater the impact of a technology, the greater its negative consequences will be.

Who will nature serve?

OK. Now back to biotech.

The biotech world also has its fair share of examples where biases, values, and context have shaped the use and/or design of a technology:

- The overrepresentation of white individuals during clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines.

- The fact that most (>75%) of the sequenced genomes we use to study human health and diseases originate from white individuals of European descent, even though this ethnic group accounts for only 16% of the global population.

- Monsanto developing pesticide-resistant GMO seeds only to end up extorting the same farmers it was supposed to help and becoming a monopoly that controls the world’s food supply (80% of U.S. corn and >90% of U.S. soybeans are grown with Monsanto’s seeds).

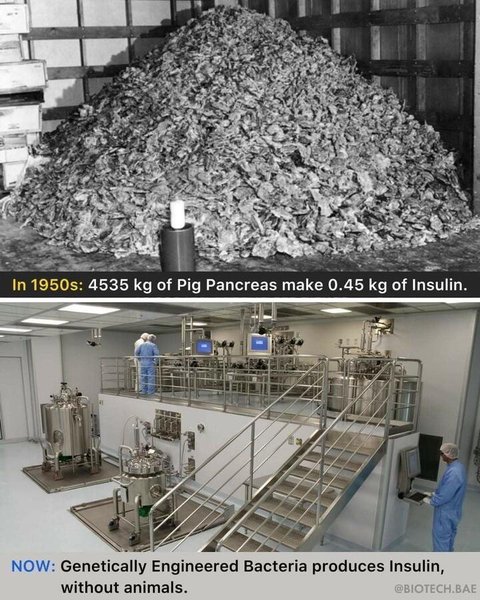

- Biomanufactured insulin increasing in price by 600% over the last 20 years, despite technological improvements meaning that a vial of human insulin now costs only $2.28 to $3.42 to produce. All a planned effort by the oligopoly of companies that control supply to increase profits at all costs, knowing that it’s a matter of life or death to the people who need insulin and they will ultimately pay whatever it costs.

I believe that this is the real dark side of the Biological Revolution. Yes, biotechnologies will likely have more of a positive impact on society than anything else. But if we fail to recognize the hidden biases and interests behind the use of biotech, its promises will benefit only a handful of people.

What happens if we allow biomanufacturing to develop under the values, culture, and biases of current extractive capitalism?

We could potentially produce as much as 60% of the physical inputs of our global economy using biology, but what if a select few corporations end up capturing this technology with the ultimate goal of increasing their profits and share values?

Biotech promises to increase longevity and cure all manner of diseases, but what if living longer is only accessible to the billionaires of the world and new drugs for diseases are only administered to the most privileged?

The Biological Revolution won’t make miracles by itself — it depends on the people who build it, and it’s our responsibility to guide it through a new system that primarily values people (from all backgrounds and places) and the planet. Otherwise, biotech may become only a tool to perpetuate the status quo.

Integrating all voices into the equation

So how do we build a Biological Revolution that takes everyone into account, minimizes the influence of biases, and ultimately delivers a better future for all? I owe you that one for now.

I don’t think that there’s a definitive answer, but a starting point would be to allow distributed access to biotechnologies (including knowledge, infrastructure, and ultimately the products and services that the bioeconomy delivers). This would prevent them from becoming centralized technologies available only in a few rich countries and amplifying the already large inequalities.

The great thing about biotechnologies is that they enable local economies. And as more people from all around the world join the Biological Revolution, the greater diversity of thoughts and contexts we’ll have to minimize the risk of biases tilting the benefits of biotech toward particular segments of the population. Ultimately each community could adapt each technology to better serve their particular requirements, but this will only be possible if they have access to it in the first place.

Another key point would be to integrate responsibility as a fundamental part of the technology design process. In her TED Talk, Cristina Zaga discussed six key principles for designing tech responsibly:

- Assess the values of your technology — including your own values and those of the people you are working for and with.

- Analyze the impact of the technology before you bring it to society.

- Seek out and listen to a diverse range of voices during the design process.

- Assess the power structures impacting the technology, as well as the privileges and economic driving forces behind it.

- Design technology for social justice and equality.

- Design for diversity and inclusiveness.

Fortunately, the Biological Revolution is already starting to take these principles into account. A great example would be the iGEM Competition, where thousands of students worldwide work on synthetic biology projects that aim to solve local problems in their communities. Teams are required to assess responsibility from the conception of their project, including possible biosafety hazards and the impacts it will have on all stakeholders.

Of course, responsible design and globalized access won’t completely prevent the misuse of biotechnologies — again, all technology comes with both blessings and burdens. However, they set the path that enables a more sustainable and equitable world for all.

There is no doubt that the world won’t be the same after the Biological Revolution, and this is only the beginning, so we had better design it to be fair.

An earlier version of this article first appeared on Substack.