Seaweed Aquaculture's Untapped Potential

October 12, 2021 - 5 min read

Featured

Seaweed aquaculture is the world’s fastest-growing food sector, with its yearly production volume growing at a rate of 8-10%. More people are discovering that farming seaweed is a viable livelihood, and the number of its applications is growing as the body of research on its uses expands into food, feed, fertilizer, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals, textiles, pigments, plastics, construction materials, and more. As the world frantically seeks to decarbonize, seaweeds have increasingly been touted by scientists and entrepreneurs alike as a critical piece of the puzzle.

Meanwhile, in the alternative protein space, it’s the potential of microalgae that has thus far received the majority of the attention. These microscopic biological cousins of seaweed (itself a macroalgae) are currently being explored by a number of startups working on cell-culture media for cultivated meat, and as ingredients in plant-based meat products, animal feed, and other food applications.

But controlled cultivation of microalgae often requires expensive facilities with advanced equipment and a highly educated staff to operate. Seaweed, on the other hand, can be cultivated in open bodies of water, such as the ocean. Although seaweeds have been consumed for millennia, they’re increasingly (and rightly) viewed as a hero ingredient. Let’s take a closer look at their significant untapped potential in the alt-protein space.

The environmental benefits of seaweed aquaculture

The foremost (and most self-evident) benefit is that seaweeds grow in the ocean and so they don’t require fertile soil or fresh water to grow — both of which are resources in increasingly short supply.

Notably, seaweeds take up nutrients from the water; no pesticides or fertilizers need to be added. They can be grown as part of a polyculture — with shrimp or salmon farms, for instance, where the seaweeds absorb the excess nutrients from these animals — or they can help clean up the excess fertilizer from agricultural wastewater run-off that washes into the sea, a process known as bioremediation.

Furthermore, seaweeds are algae, and algae were the original photosynthesizers before they crawled on land and turned into plants and trees. This means they take up carbon dioxide. The picture around the carbon sequestration potential of seaweed aquaculture will take a bit longer to form but, at a minimum, seaweed offers great potential to decarbonize existing industries by replacing petroleum-derived products with, for instance, seaweed-based bioplastics.

Seaweed farms also provide habitat and a nursery for fish, increasing biodiversity by 40% and species abundance by 30%, according to a recent TNC study. Farms can also serve as a coastal defense, acting as living breakwaters, which might help mitigate future flooding risks as ocean levels rise.

Finally, seaweed farming provides income to millions of families in rural coastal communities in Asia and Africa. In most developing countries, the majority of people involved with seaweed farming are women, with men often preferring the fast daily income that fishing brings. This has enabled women to become economically active and achieve a degree of independence and emancipation that was not available to them before, in areas where few opportunities exist. Further, while initially less lucrative than daily fishing income due to the steep and often protracted learning curve involved in farming and cultivation, these “seaweed women” ultimately enjoy a more stable income which can balance the effects of fishing’s unpredictable outcomes on household finances.

Wild seaweed stocks do not allow for further growth, meaning seaweed aquaculture is the only way forward for the industry to grow. For now, seaweed farming outside Asia is minimal but there is a concerted push to make the seaweed industry succeed across the world. Whether it’s Australia, Canada, Belize, Brazil, Norway, or Namibia, pioneering governments, scientists, and entrepreneurs are looking to build up this new industry.

Seaweeds in the alternative protein industry

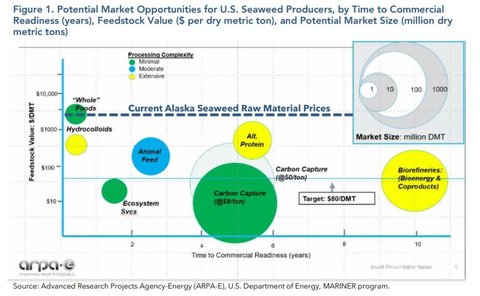

The ability to extract proteins from seaweed to create drop-in protein pastes has been proven in the lab but is still in its infancy. A look at the graph below from the Alaska Seaweed Market Assessment report shows that 2026 is a reasonable aim for this technology to be commercially ready.

Pending the development of technologies to commercialize seaweed protein extracts and concentrates, alternative protein startups have focused on adding whole seaweed to their products. Trophic, for instance, is about to come to market with a bacon replacement made from dulse.

Comfort foods that could benefit from a boost of seaweed’s umami profile are a natural fit and burgers are an obvious starting point for an alt-protein startup. Started in 2013 as a food truck, The Dutch Weed Burger was the first company to produce a soy-based patty enriched with kombu. The company went from food truck festivals to supermarket shelves and was recently acquired by The LiveKindly Collective with the intent to scale up and expand beyond its national borders. Chilean company Quelp has a similar burger on offer.

In the US, Akua raised more than $1M for its kelp burger through crowdfunding. Meanwhile, Trophic, the company working on dulse-based bacon, has created a process for extracting a 65% protein concentrate from red seaweed. The company says the non-protein substances can be useful ingredients for meat substitute products by contributing color, flavor, and vitamins.

Other startups currently in the R&D phase are Born Maverick, developing shrimp and scallop replacements from seaweeds, and Plantruption, also coming out with a seaweed burger. A company that’s instead taking the hybrid route is Umameats. By adding seaweeds to traditional meat products, Umameats wants to elevate their taste and nutritional profile.

Meanwhile, in the cell-based space, seaweed is being used by Korean startup Seawith as scaffolding for its structured cultivated meat products.

This is just the start

Seaweed is the collective noun for a group of at least 10,000 species of macroalgae, and new ones are being discovered each year. With only half a dozen species cultivated at scale right now, seaweed’s potential for the alt-protein industry is only just starting to unfold.

Agriculture has had a 10,000-year head start on sea farming. It’s time for a little catch-up.

Steven Hermans reports on the emerging seaweed economy at Phyconomy.