Microalgae as a Protein Source for the Future

December 19, 2023 - 8 min read

Featured

Explainer

Microalgae, those tiny organisms that thrive in water and sunlight, hold immense potential for addressing the world’s protein sustainability challenges. Despite their diminutive size, these microscopic powerhouses offer a wealth of amino acids and other nutrients. With protein contents typically ranging from 30% to 80% — figures that surpass those of common sources such as dried skim milk, soy flour, chicken, fish, and peanuts — it’s not only the quantity of protein per unit of biomass that’s impressive, but also the quality. Several microalgal species are known to possess amino acid profiles that meet or exceed FAO standards for a well-balanced protein source, with some notable species including Arthrospira platensis, Dunaliella salina, and Galdieria sulphuraria.

However, these remarkable nutritional profiles come with an important caveat: raw microalgal biomass is not always readily digestible by humans. As such, like most other food and protein sources, some processing or preparation may be needed. For many microalgae, digestibility can be improved through pre-treatment techniques, allowing for consumption directly as biomass or as protein extracts. Just as with plants, the specific treatment needed varies with the species. Cyanobacteria like A. platensis, for instance, show higher digestibility than green algae such as Chlorella, which feature a more robust cell wall that must be broken before consumption.

While nutrition and digestibility are crucial for any crop to be a viable food source, these properties alone are not sufficient — safety and palatability must also be considered. For example, microalgal biomass is known to be high in nucleic acids, the excessive consumption of which can lead to gout and kidney stones. Although the nucleic acid levels of microalgae are typically lower than those of faster-growing microbes such as yeast and bacteria, keeping the nucleic acid content in check remains crucial. Furthermore, the chlorophyll content of microalgae can impact consumer acceptance on account of its color and taste. But this is also manageable, as removing chlorophyll can be achieved through mild treatment steps or by selecting “pale” strains with lower (or zero) chlorophyll contents.

While these issues can all be addressed by selecting the right species and strain and understanding its specific treatment requirements, they are also influenced by the cultivation method and conditions.

Cultivation for protein yield

Microalgae are photosynthetic organisms — their primary sources of energy and carbon are sunlight and carbon dioxide (CO2). Like plants, microalgae also need a steady supply of water and nutrients to grow. For this reason, it has often been suggested that microalgae production could utilize waste streams from the food and feed industries, which are readily available and rich in inorganic nutrients. In theory, this would allow microalgae to double as both a food source and a waste treatment technology. However, such a strategy remains challenging, as it would only be feasible for waste streams of sufficiently high quality and consistency. In practice, the large-scale cultivation of microalgae for food applications may be forced to rely on inorganic fertilizers, similar to those used in conventional agriculture.

Moreover, to produce food-grade microalgae products, strictly controlled cultivation conditions are essential. At a minimum, this means adhering to third-party standards and certification schemes such as good manufacturing practices (GMP) and good agricultural practices (GAP). Currently, the most common microalgae production systems are raceway ponds and closed tubular photobioreactors. While raceway ponds may be constructed inside greenhouses to reduce environmental variation, closed tubular photobioreactors offer far greater levels of control. Contained production systems, such as photobioreactors, are not only necessary for GMP certification but also feature the added benefit of efficient fertilizer utilization, which can be as high as 100%. This allows for a significant reduction in environmental pollution compared with many other protein-rich food crops.

Finally, sunlight is the driving force behind microalgal growth, and productivity depends largely on the light supply rate, which varies by location.

Depending on these inputs, biomass productivity can range from 12 to 24 grams per square meter per day — approximately 22–44 metric tons of single-cell protein per hectare annually, assuming a 50% protein content. This compares very favorably to soybean, which yields approximately 1.2 metric tons of protein per hectare.

Making microalgae affordable

While microalgae hold great potential as a food source, their large-scale application remains constrained by high production costs. Initial capital investments in equipment and the recurring costs of materials, reagents, energy, CO2, and oxygen removal all contribute to restrictive prices for the final products. One analysis estimated a production cost of 5–9 euros per kilogram of dry algal biomass when using tubular photobioreactors and nonrenewable CO2. This translates to approximately 10–18 euros per kilogram of dry protein mass, not accounting for additional processing costs.

Cost reduction strategies primarily focus on improving the photosynthetic efficiency and addressing CO2 supply challenges. While LED lighting has been considered as one possible approach for accomplishing the former goal, the gains are currently outweighed by added electricity expenses, making direct sunlight the most cost-effective light source for the foreseeable future.

Maintaining high dissolved CO2 levels is the other fundamental challenge. This requires supplying a CO2-rich gas stream, as well as production systems engineered to minimize losses from liquid–gas transfer. Direct air capture of CO2 from the atmosphere is a promising technology that could enable the cost-effective growth of microalgae in tubular photobioreactor systems — current estimates indicate an added cost of just 0.18 euros per kilogram of dry algal biomass with respect to the use of nonrenewable CO2. However, this technology is still under development and industrial-scale systems are not yet available.

Another significant cost can be the energy required to maintain the optimal temperature for microalgal growth. This cost can be reduced, at least to some degree, by selecting species and strains suitable for the climates in which they are being cultivated and rotating algal crops according to seasonal variations in temperature. Harvesting microalgae can be also energy- and capital-intensive owing to the small cell size and dilute culture, for which technologies like filtration and centrifugation become cost effective only at a large scale.

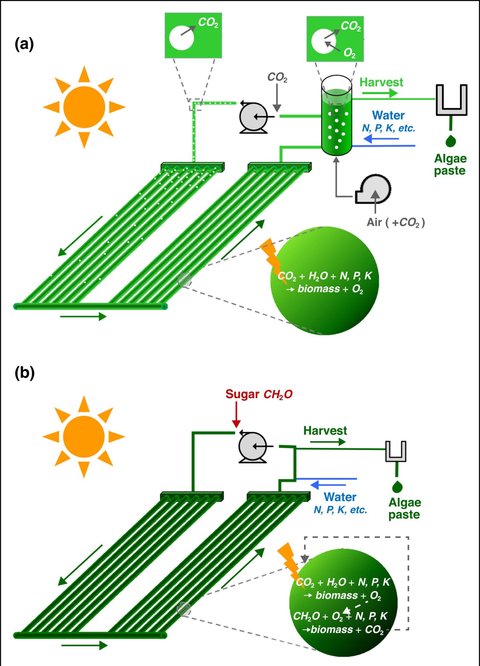

Mixotrophic cultivation

When CO2 and light are the drivers of microalgal growth, it is called autotrophy. However, many species have flexible metabolisms that enable them to also grow on organic sources of carbon, such as glucose, lactose, or other agri-food side streams, in the absence of light. This type of growth is known as heterotrophy. When both autotrophic and heterotrophic methods are used simultaneously, it is referred to as mixotrophy. Mixotrophic growth is an alternative approach to the cultivation of microalgal biomass and other single-cell proteins. Some species, like those of the Chlorella genus and G. sulphuraria, are especially well suited to this type of production, which can increase biomass concentrations by as much as twofold, reducing overall costs and making harvesting more efficient.

Galdieria sulphuraria and Chlorella species are just two examples of species able to grow on organic carbon. However, on an industrial scale, the utilization of commercially available sugars such as glucose would carry environmental burdens associated with the agricultural production of the crops used to make them. To realize a truly sustainable and scalable process for microalgae production, alternative carbon sources must be considered.

Fortunately, much work has already been carried out in the field of microalgae-based waste treatment, and the resulting knowledge can be used to understand the abilities of different species to grow on various carbon sources. For example, some microalgae have been shown to grow well on acetate and glycerol, which are inexpensive and readily available industrial byproducts. Another approach is to assess the potential of food industry side streams that do not currently meet regulatory requirements for food safety, but which could be used to support microalgal growth in a sustainable manner.

The versatility of microalgae allows them to grow under a wide range of conditions, and mixotrophy is an elegant solution that combines the advantages of both autotrophy and heterotrophy. However, because adding organic carbon on an industrial scale increases the probability of contamination by other microorganisms, mixotrophic production for food applications requires closed systems to maintain rigorous controls for product quality and safety. Food safety risks can also be minimized by selecting the appropriate species for the desired application. Some extremophile species such as G. sulphuraria, for instance, are able to grow in extremely harsh conditions — pH 1.0 and temperatures up to 50 degrees Celsius — under which very few other microorganisms are able to survive.

A promising path for sustainable protein production

Alongside energy, protein is gaining increasing recognition as the world’s other major sustainability problem. By addressing key cultivation challenges and exploring alternative growth strategies such as mixotrophy, microalgae are emerging as a promising solution. These powerful microorganisms outperform many common protein sources in terms of land and water requirements, and they offer a wealth of nutritional advantages. As research evolves and the industry develops, microalgae-based protein products may become more accessible to consumers, providing a valuable addition to our diets and food supply chains.

This article is based on the February 2022 open-access article “Microalgae based production of single-cell protein” published in Current Opinion in Biotechnology. All of the images used in this article were taken from this source and are reproduced here according to the original article’s Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.