Protein Literacy Basics: Antimicrobial Resistance

April 27, 2021 - 8 min read

Featured

Explainer

This article is part of our Protein Literacy series, a collection of explainers and educational tools exploring key protein industry challenges and possible solutions.

What is antimicrobial resistance and why is it a problem?

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when microbes develop the ability to survive or grow in the presence of the drugs designed to kill them. This renders existing medicines less effective at fighting infections, which means those infections become more deadly.

According to the CDC, “Each year in the U.S., at least 2.8 million people get an antibiotic-resistant infection, and more than 35,000 people die.” Worldwide this figure is 700,000 deaths, and the Antimicrobial Resistance Industry Alliance projects that number will rise to 10 million by 2050. The Director-General of the World Health Organization, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has said “a lack of effective antibiotics is as serious a security threat as a sudden and deadly disease outbreak.”

The effects of such infections are not just health related; one strain of antibiotic-resistant bacteria alone classified as “urgent” by the CDC was associated with $281 million in healthcare costs in 2017. Global healthcare costs incurred due to antibiotic-resistant infections are expected to reach $1 trillion per year by 2050.

Drug-resistant pathogens not only compromise human health, they also jeopardize the well being of livestock and wildlife populations that play vital roles in the environment. For this reason, the CDC calls antibiotic resistance a One Health challenge in which “the health of people is connected to the health of animals and the environment.”

How does antimicrobial resistance work?

Antimicrobial resistance happens when germs are exposed to drugs, develop mechanisms of resistance against those drugs, and pass on these mechanisms to other members of their population. By the principle of natural selection, when exposed to a drug, the germs that survive are those that contain a mutation more effective at withstanding the drug. These germs then outlive their ill-adapted counterparts, reproduce more, and their mutation becomes characteristic of the entire population. The more a given drug is used, the more opportunities a germ species has to evolve a characteristic that can resist it.

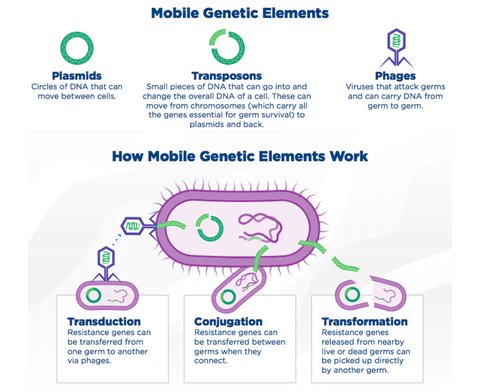

In addition to inheritance of these traits as the result of evolution within a population, resistant elements can also be transferred between individual bacteria. This happens through the sharing of the mobile genetic elements which are responsible for resistance mechanisms including plasmids, transposons, and phages which can be integrated into another germ cell through transduction, conjugation, or transformation.

The process of microbes becoming resistant to drugs is naturally occurring, but it is expedited when those drugs are constantly present in an environment. This can happen through the overuse of fungicides and pesticides in commercial agriculture, as well as with antibiotics used to treat infections in patients and mitigate the spread of disease among livestock.

For instance, penicillin was the first commercialized antibiotic discovered in 1941 by Alex Flemming and was widely used during the second half of the twentieth century. During that time, three significant germs developed that were resistant to penicillin: Staphylococcus aureus in 1942, Streptococcus pneumoniae in 1967, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in 1975. This has limited the modern use of penicillin and related drugs today.

According to the World Economic Forum, the overuse of antibiotics is “leading us into a post-antibiotic world in which people will once again die from common infections and minor injuries.”

What does it have to do with protein?

Although antibiotics are generally thought of in the context of treating infections within our healthcare systems, that’s not where most of the world’s antibiotics are actually used.

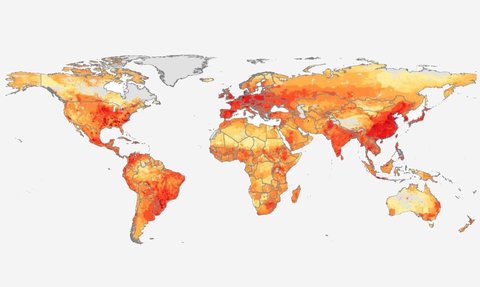

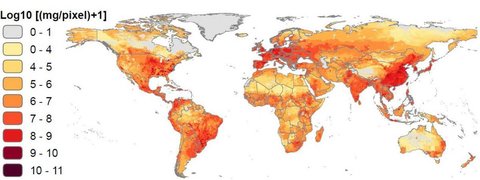

In the United States, more than 70% of all medically important antibiotics are used in livestock, while in Canada more than 80% of all antibiotics are used in agriculture. Globally, around 73% of all antibiotics are used in animals grown for food. By 2030, the total amount of antimicrobials used in food animals is projected to increase by as much as 53% over 2013 levels.

Why are farm animals consuming so many antimicrobials?

“The high population density of modern intensively managed livestock operations results in sharing of both commensal flora and pathogens, which can be conducive to rapid dissemination of infectious agents. As a result, livestock in these environments commonly require aggressive infection management strategies,” explains Timothy F. Landers et al in a 2012 paper. They go on to detail how antibiotics are not only used to treat and prevent disease in such environments, but are also used to enhance animal growth.

According to the FAIRR Initiative, an investor network worth $38 trillion, “To be profitable, companies have relied on the routine mass medication of farm animals with antibiotics, both as a means to increase feed efficiency and to reduce mortality.” In their Protein Producer Index, FAIRR ranks 60 of the world’s largest meat, fish, and dairy producers and has found 70% to be “high risk” for antibiotics, indicating “extremely poor levels of antibiotic stewardship.”

As explained by the Director of the Department of Food Safety and Zoonoses at WHO, Dr. Kazuaki Miyagishima, “scientific evidence demonstrates that overuse of antibiotics in animals can contribute to the emergence of antibiotic resistance. The volume of antibiotics used in animals is continuing to increase worldwide, driven by a growing demand for foods of animal origin, often produced through intensive animal husbandry.”

Some stakeholders argue that strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria which develop in farm animals do not pose risks to human health. However, other researchers have found decades of evidence indicating otherwise. In their 2012 paper, Timothy F. Landers et al cite studies showing “Associations between antibiotic use in food animals and the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria isolated from those animals have been detected in observational studies as well as in randomized trials. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria of animal origin have been observed in the environment surrounding livestock farming operations, on meat products available for purchase in retail food stores, and as the cause of clinical infections and subclinical colonization in humans.”

The CDC also notes that “when animals are slaughtered and processed for food, resistant bacteria can contaminate meat or other animal products” leading to antibiotic-resistant intestinal infections if these foods are handled or consumed. For example, a notable February 2019 American outbreak of a multidrug resistant strain of salmonella was linked to the consumption of raw and undercooked chicken.

Overuse of antibiotics in livestock doesn’t only risk contaminating food products. Up to 90% of antibiotics ingested by livestock are secreted in urine and waste which is then dispersed in fertilizer and surface runoff contributing to diffuse environmental contamination. In 2019, the first global study of antibiotics in the world’s rivers found that two thirds of the world’s rivers are polluted by antibiotics with certain concentrations exceeding 300 times above what is considered safe.

How can antimicrobial resistance be mitigated?

In 2019, the CDC’s AR Threats Report listed 18 resistant germs as either “urgent,” “serious,” or a “concerning threat.” In order to mitigate the further development and spread of antibiotic resistance, they recommend improving antibiotic use so they are administered only when necessary rather than as a routine procedure.

In the United States, the USDA along with the FDA and EPA administers the US National Residue Program which attempts to reduce the amount of antibiotic residues (small quantities of unabsorbed antibiotics) entering the food supply. Since 2006, the European Union has banned the use of antibiotics for growth promotion. The WHO also suggests that “antibiotics used in animals should be selected from those listed as being ’least important’ to human health, and not from those classified as ‘highest priority’ and ‘critically important.’”

But policy isn’t the only available lever for addressing the problem — investors and food producers also have a role to play.

According to the FAIRR Initiative, “Investors now recognise that the routine non-therapeutic use of antibiotics in livestock production is a leading cause of rising antimicrobial resistance worldwide.” They report that between 2010 and 2019, 24 shareholder resolutions on antibiotics overuse in livestock have been filed in the United States. FAIRR has also developed a Best Practice Policy for food producers and retailers, and coordinated a global investor statement on antibiotics stewardship whose signatories include 75 investors managing over $3 trillion in assets. In 2020, FAIRR, along with the Access to Medicine Foundation, PRI, and the UK Government, launched Investor Action on AMR, a new initiative to leverage investor influence to combat drug-resistant superbugs.

The issue is also starting to see some push coming from the public; many consumers are increasingly favoring meat products with label claims such as “No Antibiotics Ever,” “Raised without Antibiotics,” and “No Added Antibiotics.” But such all-or-nothing approaches are probably not the solution — after all, just like humans, animals also sometimes get sick and need medicine.

In a 2017 article published in Science, an international group of biologists, policy, and disease specialists proposed a three-pronged approach to reducing antimicrobial use in livestock in order to mitigate the development of drug-resistant infections in humans and animals. Through a combination of policies that cap permissible levels of veterinary antibiotic consumption, reduce meat consumption, and raise the cost of veterinary antimicrobials, the global use of antimicrobials in food animals could be lowered by as much as 80% by 2030. Even if only the countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and China implemented just some of these strategies, global antimicrobial use in animals could be reduced by as much as 60%.