UC Davis Sets Its Sights on the Main Course

March 24, 2021 - 8 min read

Featured

The school that helped turn California’s wine industry from afterthought into economic juggernaut has set its sights on cultivated meat.

How do you feed 10 billion people? It’s a question that intrigued Dr. David Block, professor and Marvin Sands department chair of the viticulture and enology programs at the University of California Davis (UC Davis). It’s also a question that won’t be hypothetical for much longer. As Block explained in the school’s recent public webinar, “Growing Real Beef Without the Moo,” in order “to be able to feed 10 billion people simultaneously in 2050, we’ll need to produce as much [food] over the next 50 years, as we have in the history of humanity up to this point.”

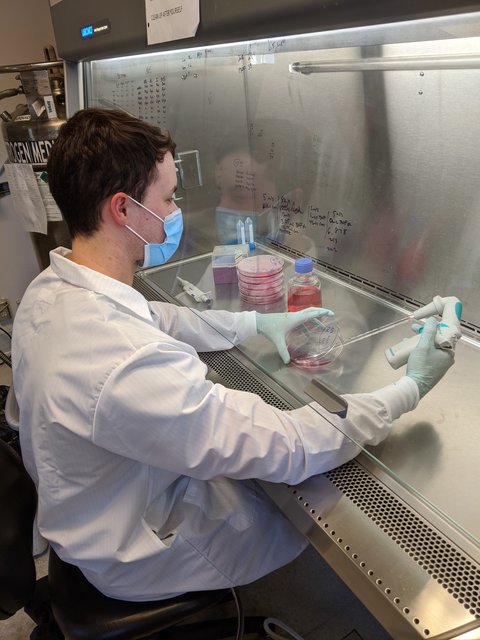

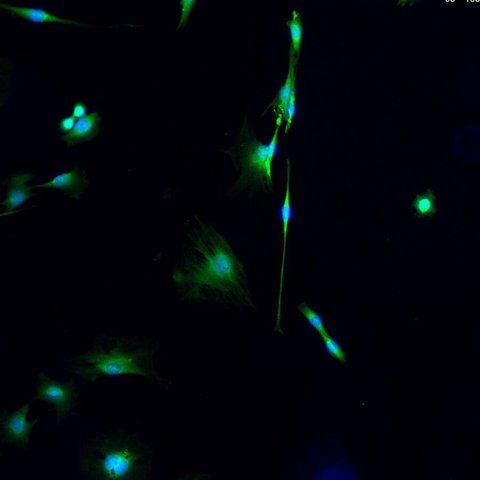

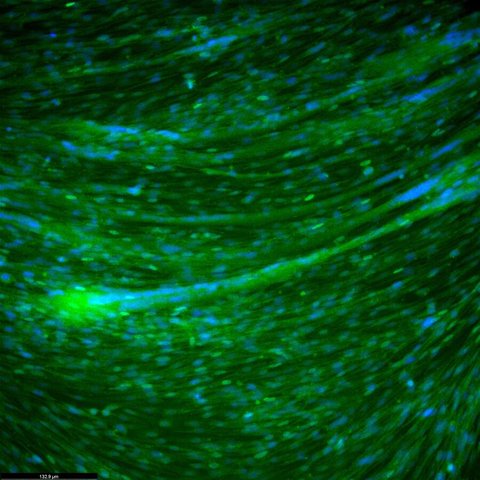

One of the possible solutions researchers are working on is the development of cultivated meat. If you aren’t yet familiar with the concept, don’t fret; it seems the industry itself hasn’t quite decided which term—cultivated, cultured, cell-based, slaughter-free, or clean meat—to land on. Whatever the name, though, the process to create it is the same: scientists extract cells from animals and nourish those cells in an optimal mix of growth media (more on this later) to the point of what scientists call “differentiation” (they become muscle or fat cells, for instance) until the end product can be harvested as meat. Unlike recent alternative protein advancements that have led to products like Beyond Meat or the Impossible Burger, cultivated meat is real meat. But whether it can feed an exploding population better than its conventionally produced counterpart is, like many other billion-dollar ideas, largely a question of scalability.

UC Davis is now the first public institution to receive federal funds for research that will attempt to answer that question. The Northern California school was recently awarded a five-year grant by the National Science Foundation (NSF) for up to $3.55 million through its “Growing Convergence Research” program. Not only does the grant represent the first federal funds earmarked to aid in cultivated meat research, its selection criteria actually had nothing to do with cellular agriculture, as Block was careful to point out during his portion of the presentation. Instead, the NSF invited researchers to propose solutions to compelling social problems. And what could be more compelling—and urgent—than trying to figure out how to feed 10 billion people.

Though cultivated meat was little more than speculation five years ago, it’s already become reality, albeit one with a caveat. To paraphrase futurist and author, William Gibson, the future of meat is already here—if unevenly distributed. While many labs have successfully created cultivated meat, most private labs are engaged in a race to market that precludes the sharing of processes and results; industry insiders believe these independent labs may be doing research and development that’s the cultivated meat equivalent of reinventing the wheel.

There’s currently only one restaurant in the world—a tony, members-only club in Singapore—that offers cell-based chicken on its menu. But if cell-based meat does hold the answer to feeding billions more people, it needs to be much more accessible. That’s one of the reasons many in the alt protein community (the term applied to the loose collection of companies creating alternatives to traditionally animal-based foods) are excited by the promise of the NSF grant. Not only is its award a tacit endorsement of cultivated meat research, UC Davis’s work will represent a new open science approach to cultivated meat, one where research findings will be publicly shared, instead of siloed by the need for race-to-market secrecy.

It was a presentation by a speaker from the Good Food Institute (GFI) at a 2018 convention of food innovation and engineering that first piqued Block’s interest about the problems associated with meat production, as well as the untapped possibility. Around the same time, two of Block’s PhD students, Ted O’Neil and Zach Cosenza, came to him with an interest in working on cell-based meat media optimization, the life science process for creating the most auspicious environment for cellular growth.

Sensing an opportunity, Block’s graduate students quickly secured two grants with the cellular agriculture research institute New Harvest in 2019, and Block received a third grant from GFI in early 2020 to begin research into alternatives to conventional meat production. At the end of 2019, the school established the UC Davis Cultivated Meat Consortium, a multi-disciplinary group of 30 researchers who were all interested in the nascent field of cultivated meat. School researchers have been quick to point out, however, that the university views cultivated meat as a market supplement to and not a replacement for conventionally farmed meat—an important distinction at a school with deep farming roots where the student population is known as the “aggies.”

As a land-grant institution that arguably put the California wine industry on the map (partly by creating a school-to-industry talent pipeline), UC Davis is uniquely positioned to deliver on the promise of cell-based meat. As Block put it when explaining his areas of research, cultivated meat “requires the deep integration of stem cell engineering, tissue culture, animal and meat science, experimental process optimization and artificial intelligence, biochemical engineering, industrial fermentation and manufacturing, food science and engineering, materials science and biomaterials, sensory science, techno-economic modeling, life cycle analysis, and consumer science.”

By taking a multidisciplinary approach to its research, UC Davis has the potential to rally public resources for public good in a way that’s not before been applied to the science of cultivated meat—all while integrating principles from the school’s noted winemaking and biotech programs to the new research.

Aside from the promise of what open research could mean to the advancement of cultivated meat, the product may also benefit from a surprisingly well-worn path to regulatory approval. As Eric Schulze, vice president of product and regulation at cell-based meat startup Memphis Meats and co-presenter alongside Dr. Block at the recent presentation, noted, “The FDA and USDA are not doing anything new [with regard to future product regulation]. They’re using existing pathways to regulate the safety of these products.” So while the idea of cultivated meat may require some consumer education to get potential customers to see it as something other than “lab-grown meat” (a term the industry abhors), the actual scientific processes at play are not unknown to the federal regulators who’ll be assessing its safety.

According to Dr. Denneal Jamison-McClung, Director of the UC Davis Biotech Program and co-founder of the UC Davis Cultivated Meat Consortium, “A lot of the technologies around cellular meat are things that have been adapted from other biotech industries like industrial enzymes or […] tissue culture for biomedical purposes.”

Those industries, however, tend to have much deeper pockets than their food counterparts and product costs offset by insurers. So while we may be inching closer to the day a few years from now when we can pick up a pound of cultivated ground beef at the store, the price will need to be within reach for the average consumer.

Before cultivated meat arrives in supermarkets though, its viability is going to be tested, not just by regulators and consumer tastes but by its own current limitations. The Davis team, for instance, has several objectives they’ll be expected to meet over the next five years of the grant, including, “developing stable stem cell lines from which cultivated meat can be grown; developing inexpensive, plant-based media in which to grow the cells; and assessing the nutritional value, stability and sensory qualities of cultivated meat products.” Each of these presents its own daunting use-case scenario challenges that will need to be anticipated and overcome.

One of the most pressing issues surrounding cultivated meat research is the industry’s current reliance on the use of fetal bovine serum (FBS) as the most commonly used supplement in the nutrient broth where cells are cultured—a step in the development of cell lines that needs to happen for an undifferentiated animal cell to ultimately grow and become the tissue we recognize as meat. Currently, the extraction procedure is not just prohibitively expensive, it’s a byproduct of the slaughtering process, meaning a calf still has to die in order for researchers to use its fetal blood to create the FBS that’s used to cultivate cells. The FBS issue is something almost everyone in the cultivated meat industry seems to be working on in order to create a scalable alternative to its use.

As to the nutritional value and sensory qualities, the UC Davis team seems to be taking a pragmatic and consumer-centric approach. As Dr. Jamison-McClung put it when sharing some of the discussion among researchers, the hope is that “startup companies in this space realize that they are a food company, because a lot of time they talk like they are a tech company, like traditional biotech. And to some extent that’s true but you really, ultimately, are a food company and if nobody wants your food, they’re not really going to stay in business.”

And while UC Davis doesn’t have to worry about staying in business, it’s evident that members of its academic consortium share an appreciation for both the spotlight and the pressure the grant puts on their research and its urgency. The hope is, though, that by becoming an academic nexus for cultivated meat research and by sharing key findings, the whole industry can move much faster—and we’ll be that much closer to having another option on the dinner table.